An estimated 13 million people in the UK are living with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and, in some studies, it’s been reported that between 43-78% of people with IBS symptoms have small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), a potentially serious and common condition. In this article we explore the symptoms, potential causes, and things to consider.

What is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what are the symptoms?

IBS is a condition that affects the digestive system. The most common symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain, stomach cramps, delayed gastric emptying (known as gastroparesis, which is when the stomach becomes partially paralysed), bloating, diarrhoea or constipation. Symptoms can be intermittent, lasting days, a few weeks or months, though generally they can last years. While some doctors consider it to be a lifelong condition, others believe it need not be if the root cause is identified and a personalised approach is taken.

Other symptoms include wind, mucous in stools and an urgent need to go to the loo.

IBS can be accompanied by mood disturbances, fatigue, and an inability to concentrate.

Causes of IBS

Whilst the underlying causes of IBS are unknown, it’s been associated with stress, diet (it may be triggered by food or drink), infection, oversensitive nerves in the gut, and a family history of the condition.

The impact of stress on the gut cannot be overstated. The brain and the gut are intricately connected. We feel “butterflies” in our stomach when we’re nervous, a sign of our brain and gut communicating. Stress is linked to IBS and other serious gut conditions.

Gastrointestinal infection with bacterial, viral and parasitic pathogens is another recognised risk for the development of IBS. For example, certain microorganisms like Clostridia sp, Giardia lamblia, Blastocystis hominis, Dientamoeba fragilis, may cause IBS.

How is IBS diagnosed?

Whilst there’s no specific test for IBS, your GP might use the Rome Criteria to diagnose it, after ruling out other serious gastro-intestinal problems, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diverticulitis and colon cancer. Your GP may arrange:

- blood tests to check for conditions, such as coeliac disease

- tests on a sample of your poo to check for infections and IBD

Before we get on to what you can do for IBS, we’d like to explain a bit about SIBO.

As the symptoms of IBS can be caused by other serious conditions, if you think you might have IBS, it’s vital that you check with your GP in order to exclude other illnesses and to establish if you do indeed have IBS or not.

What is SIBO and what are the symptoms and potential causes?

SIBO can be a serious condition in which there are increased numbers or alterations in certain strains of small intestinal bacteria.

There’s a good deal of overlap in SIBO symptoms (abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhoea, and bloating) with other inflammatory bowel conditions, such as Crohn’s. SIBO may also be accompanied by pale, greasy and foul-smelling stools, nutritional deficiencies, and weight loss.

There may be a link between reduced gastric acid and SIBO. To help avoid overgrowth, there are three bacteria-killing mechanisms that occur along your gastrointestinal tract: gastric secretions, hydrochloric acid contained in gastric (stomach) acid in the stomach, and bile. Gastric secretions and hydrochloric acid create an acidic environment in your stomach that kills most bacteria. We produce less gastric acid as we get older, so age can be a risk factor for SIBO.

Bile released in your duodenum (the first part of your small intestine) provides further protection against bugs that can induce disease, known as pathogens.

Interfering with these mechanisms, for example taking acid-lowering drugs, having low stomach acid production, and having impaired or altered bile acid production, might open the door to SIBO.

How is SIBO diagnosed?

Several tests are available to investigate SIBO, although they can be hard to find on the NHS. Until recently, breath tests could only identify hydrogen- or methane-producing species, but the latest ones can also detect hydrogen sulphide producers.

How is SIBO treated?

Dietary changes, probiotics, prebiotics and drugs are commonly used to deal with the symptoms. Sometimes antibiotics like Rifamixin (or herbal antibiotics like oregano oil) and drugs to improve motility are necessary. Interestingly, some herbal therapies have been seen to be as effective as Rifamixin in SIBO. Functional medicine experts might recommend bismuth too, which has antidiarrhoeal, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties.

In the absence of testing, some doctors suggest that it may be reasonable to treat SIBO through experience, that is, trial and error, observation, and noticing what happens. If you suspect you have SIBO, you can ask your GP to refer you to a gastroenterologist on the NHS.

What to do about IBS

If you’re diagnosed with IBS by your GP, they’re likely to recommend things like exercise, suggest peppermint oil or perhaps offer medicines to help manage symptoms. Below are some other things you may want to consider if you have a diagnosis of IBS, some of which your GP may help with.

- Identifying what can help you de-stress. Examples may include mindfulness, breath work, prayer, gardening, knitting, and talking with friends.

- Testing for SIBO.

- Comprehensive microbiome stool testing to identify gut microbiome imbalances and help identify if specific strains of probiotics would be helpful, such as Bifidobacterium bifidum, Saccharomyces boulardii, and Lactobacillus.

- Chewing your food and eating slowly.

- Avoiding: wheat, gluten, grains, sugar, dairy, sugary fruits, legumes – as a trial to see if it helps.

- Considering if you’re vitamin B12 deficient. SIBO can cause a deficiency in vitamin B12, so if you’re experiencing SIBO symptoms or you’ve been diagnosed with SIBO, you might also have B12 deficiency, so it might be worth getting a test. Note: the serum B12 test (that your GP might do) measures a total amount of B12 in the blood, but it doesn’t rule out functional B12 deficiency.

- Taking a blood test to check your vitamin D level, as emerging evidence suggests, for some people, taking vitamin D supplements may help but it isn’t guaranteed as it’ll depend on the root cause of your symptoms.

IBS is very individual, so not all these suggestions may help; they simply offer avenues to explore. The goal will always be to understand the reason for your symptoms, and then you can focus on working on that perhaps with your GP or another health practitioner.

Low-FODMAP diet

You may have heard of a low-FODMAP diet, if you’ve been diagnosed with IBS. FODMAP is an acronym for Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols, which are types of carbohydrate that can make IBS and SIBO symptoms worse.

How to follow a low-FODMAP diet

When following a low-FODMAP diet, you restrict foods high in FODMAPs and replace with lower FODMAP foods like those highlighted here. Whilst low-FODMAP diets can be helpful in the short term, it’s crucial to note that they (like any other restrictive diet) aren’t meant to be continued long-term. Usually 4-6 weeks (max. 12 weeks) is enough to notice if symptoms improve. After the initial 4-6 weeks, it’s important to reintroduce foods to identify which foods trigger symptoms.

You’d be forgiven for finding low-FODMAP diets confusing or difficult to follow. To help, there are specific apps to navigate and implement low-FODMAP diets, such as Monash, which also provides support for the reintroduction stage. Alternatively, you may like the support of a Registered Nutritional Therapist or Dietician. You could also ask your GP to refer you to a dietician on the NHS to advise and help you manage a low-FODMAP diet.

Considerations when following a low-FODMAP diet

Low-FODMAP diets limit sulphurous vegetables like broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, peas, kale, onions, garlic and mushrooms. If a breath test has confirmed you have an overgrowth of hydrogen sulphide-producing bacteria, then re-introducing sulphurous veggies like those may not be good until the overgrowth is rebalanced. If you’re unable to take a breath test, you could experiment and see if reducing the amount of sulphurous veggies like those listed above help alleviate your symptoms, being careful to re-introduce them slowly when your symptoms have eased.

However, it’s important to note that sulphur-containing foods are vital for the body. For instance, they’re necessary for the hard-to-make amino acid cysteine, which is an essential component of the inflammatory response pathway, glutathione (a master antioxidant) production, and many detoxification pathways. So, whilst you might need to exclude them for a while, make sure you work to reintroduce them once the overgrowth is rebalanced.

A close look at the gut lining

“All disease begins in the gut”, according to Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine. Anything that can alter the integrity of the gut lining risks the entry of microbes and undigested food into regions where they don’t belong, and could be a contributing factor in IBS.

Increased gut permeability and inflammation

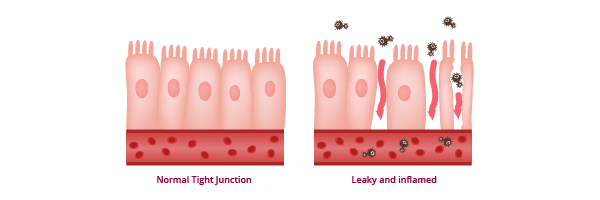

The lining of the intestines, mucous layers, its communication networks, the lymphatic gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), and neuroendocrine network, all form the gut barrier. The cells lining the gut wall are linked together by intercellular tight junctions, and these tight junctions sometimes become looser. Zonulin is a tight junction protein involved in the movement of molecules across the gut lining and can be used as an indicator of increased gut permeability (“leaky gut”). Vitamin D appears to play an important role in the maintenance of this lining.

If there’s damage to the thin mucosal gut lining, gut microbes and bowel contents can gain access to deeper layers of the gut wall, leading to an immune response – inflammation and the danger of serious infection. This increased gut permeability has been linked to the development of IBS.

How are probiotics related to gut permeability and IBS?

Probiotics, that contain beneficial live microorganisms available in capsules, powders and liquids, may help IBS by stabilising tight junctions in the gut and enhancing the barrier function of intestinal epithelial cells. They are also sometimes included in food products, such as yoghurts, fermented milk drinks and fermented foods.

Recent trials using the microorganisms Bifidobacterium bifidum, Saccharomyces boulardii and Lactobacilli demonstrated improvement in clinical IBS symptoms and quality of life, and several reviews of the evidence for the utility of probiotics in IBS have been published. For instance, L Plantarum. has been indicated to be helpful for IBS. Without testing to identify exactly what you need, using probiotics involves a certain amount of guesswork.

It’s important to note that, whilst they can be helpful, they can exacerbate symptoms. For example, some probiotics might include FODMAPs, such as inulin and FOS, which can be poorly tolerated in people with IBS. It’s recommended that you test for SIBO before taking probiotics as they can make matters worse, although some evidence has indicated that Saccharomyces boulardii can be helpful in treating SIBO. If you’re unsure, you may want to work with a Nutritional Therapist or Functional Medicine practitioner to help guide you.

Some people living with IBS or SIBO find that supporting their gut health can result in an improvement. If you haven’t already done them, look out for your notifications for our Gut Health Check and Gut Microbiome Check in the Evergreen Life app. Completing them will help you to see where you could improve your gut health, with practical tips shared along the way.

Reviewed by:

Dr Brian Fisher MBBch MBE MSc FRSA – Clinical Director

Anna Keeble MA BA Wellbeing Expert

- Bashashati M, Moossavi S, Cremon C, et al. (2017) Colonic immune cells in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 30: e13192. (doi: 10.1111/nmo.13192).

- Bowman BA and Russell RM (2006) Present Knowledge in Nutrition Ninth Edition. International Life Sciences Institute Volume 1: 308.

- Bures J, Cyrany J, Kohoutova D, et al. (2010) Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 16: 2978-90 (doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.2978).

- Chedid V, Dhalla S, Clarke JO, et al. (2014) Herbal Therapy is Equivalent to Rifaximin for the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Global Advances in Health and Medicine 3: 16-24 (doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2014.019).

- Clapp M, Aurora N, Herrera L, et al. (2017) Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clinics and Practice 7: 131-136

- Dr Davis Infinite Health Inner Circle (n.d.) Special Protocols: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). Dr Davis Infinite Health Inner Circle.

- Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, et al. (2002) AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. American Gastroenterological Association 123: 2108-2131 (doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095).

- Fakhoury HMA, Kvietys PR, AlKattan W, et al. (2020) Vitamin D and intestinal homeostasis: Barrier, microbiota, and immune modulation. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2000: 105663 (doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105663).

- Fasano A (2012) Intestinal permeability and its regulation by zonulin: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10: 1096-100. (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.012).

- Fasano A (2020) All disease begins in the (leaky) gut: role of zonulin-mediated gut permeability in the pathogenesis of some chronic inflammatory diseases [version 1; peer review: 3 approved]. F1000Research 2020, 9: 69 (doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20510.1).

- García-Collinot G, Madrigal-Santillán EO, Martínez-Bencomo MA, et al. (2020) Effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii and Metronidazole for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Systemic Sclerosis. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 65: 1134-1143 (doi:10.1007/s10620-019-05830-0 ).

- Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (n.d.) IBS and the low FODMAP diet. NHS.

- Grover M (2014) Role of gut pathogens in development of irritable bowel syndrome. Indian J Med Res. 139: 11-18.

- Holland K and Sethi S (2021) Understanding Crohn’s Disease. Healthline.

- Konturek PC, Brzozowski T and Konturek SJ (2011) Stress and the gut: Pathophysiology, Clinical Consequences, Diagnostic Approach and Treatment Options. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 62: 591-599.

- Krammer H, Storr M, Madisch A, et al. (2021) Irritable bowel treatment with Lactobacillus plantarum 299v: Prolonged use increases treatment success – Results of a non-interventional study. Z Gastroenterol. 59: 125-134 (doi: 10.1055/a-1340-0204).

- Kresser C (2022) Why B12 Deficiency Is Significantly Underdiagnosed. Chris Kresser.

- Kubala J, Moore K, Goldman R, et al. (2020) 12 Foods to Avoid with IBS. Healthline.

- Losurdo G, Salvatore D’Abramo F, Indellicati G, et al (2020) The Influence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Digestive and Extra-Intestinal Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 21: 3531 (doi: 10.3390/ijms21103531).

- Medichecks (n.d.) Vitamin D (25 OH) Blood Test. Medichecks.

- Merritt ME and Donaldson JR (2009) Effect of bile salts on the DNA and membrane integrity of enteric bacteria. Journal of Medical Microbiology 58 (doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.014092-0).

- Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, et al. (2010) The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Gut 59: 325-332 (doi:10.1136/gut.2008.167270).

- Monash University (n.d.) High and low FODMAP foods. Monash University.

- Monash University (n.d.) The low FODMAP diet. Monash University.

- NHS (2019) Overview Coeliac disease. NHS.

- 26.NHS (2021) Getting diagnosed. NHS.

- NHS (2021) What is IBS? NHS.

- NHS (n.d.) Remote monitoring of patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, IBS and food intolerances. NHS.

- Ponziani FR, Gerardi V and Gasbarrini A (2015) Diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 10: 215-227 (doi: 10.1586/17474124.2016.1110017).

- Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard H-C, et al. (2016) Irritable bowel syndrome, the microbiota and the gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes 7: 365-383 (doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1218585).

- Ruiz AR Jr. (2021) Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). MSD Manual Consumer Version.

- Ruscio M (2018) Treating SIBO with a High FODMAP Diet & Higher Carb Intake – How Hydrogen Sulfide SIBO Breaks The Rules with Dr. Nirala Jacobi. Dr. Ruscio DNM, DC, Blog.

- Ruscio M (2021) What’s the best SIBO breath these and how do I know if I need one? Dr Ruscio’s Clinic The Ruscio Institute for Functional Medicine.

- Ruscio M (n.d.) What Is Hydrogen Sulfide SIBO and How Is It Treated? Dr. Ruscio DNM, DC, Blog.

- Stark D, Van Hal S, Marriott D et al. (2007) Irritable bowel syndrome: A review on the role of intestinal protozoa and the importance of their detection and diagnosis. International Journal of Parasitology 37: 11-20 (doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.09.009).

- Thazhath SS, Haque M and Florin TH (2013) Oral bismuth for chronic intractable diarrheal conditions? Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology 6: 19-25. (doi: 10.2147/CEG.S41743).

- Williams CE, Williams EA and Corfe BM (2018) Vitamin D status in irritable bowel syndrome and the impact of supplementation on symptoms: what do we know and what do we need to know? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 72: 1358–1363 (doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0064-z).

- Wright CP, Dooley MT and Leeson H (2021) Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome using herbal therapy: A case report. International Journal of Functional Nutrition 2 (doi: 10.3892/ijfn.2021.23).

- Yoon SS and Sun J (2011) Probiotics, nuclear receptor signaling, and anti-inflammatory pathways. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011: 971938 (doi: 10.1155/2011/971938).

- Zhao L, Yang W, Chen Y, et al (2020) A Clostridia-rich microbiota enhances bile acid excretion in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2020: 130: 438-450 (doi: 10.1172/JCI130976).